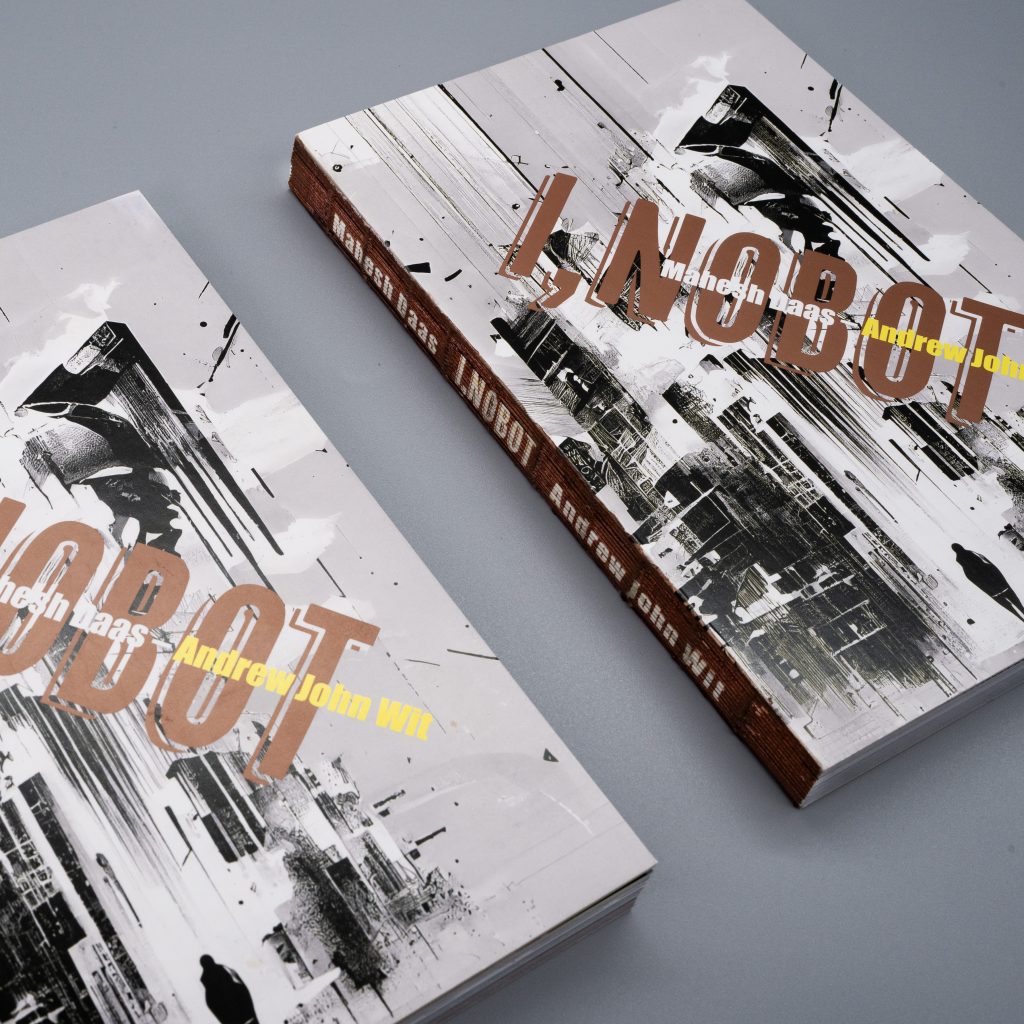

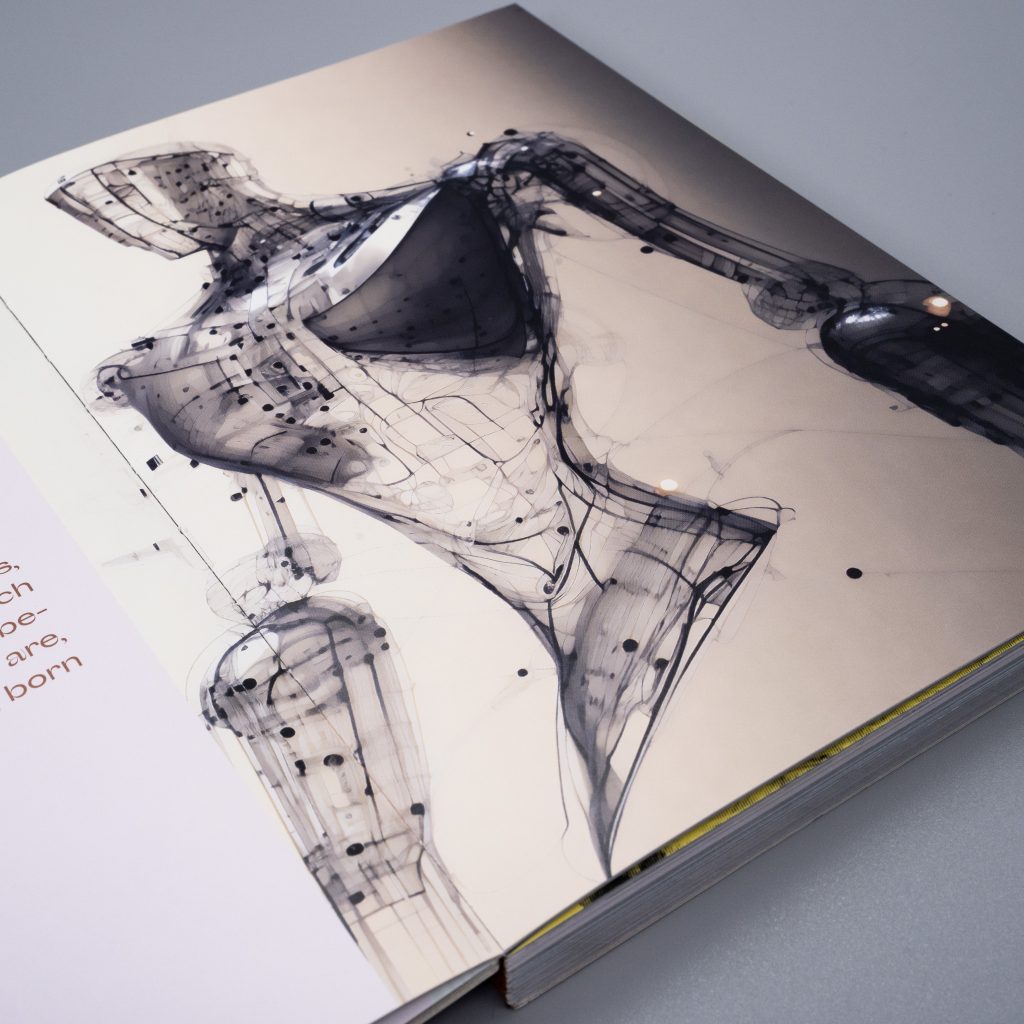

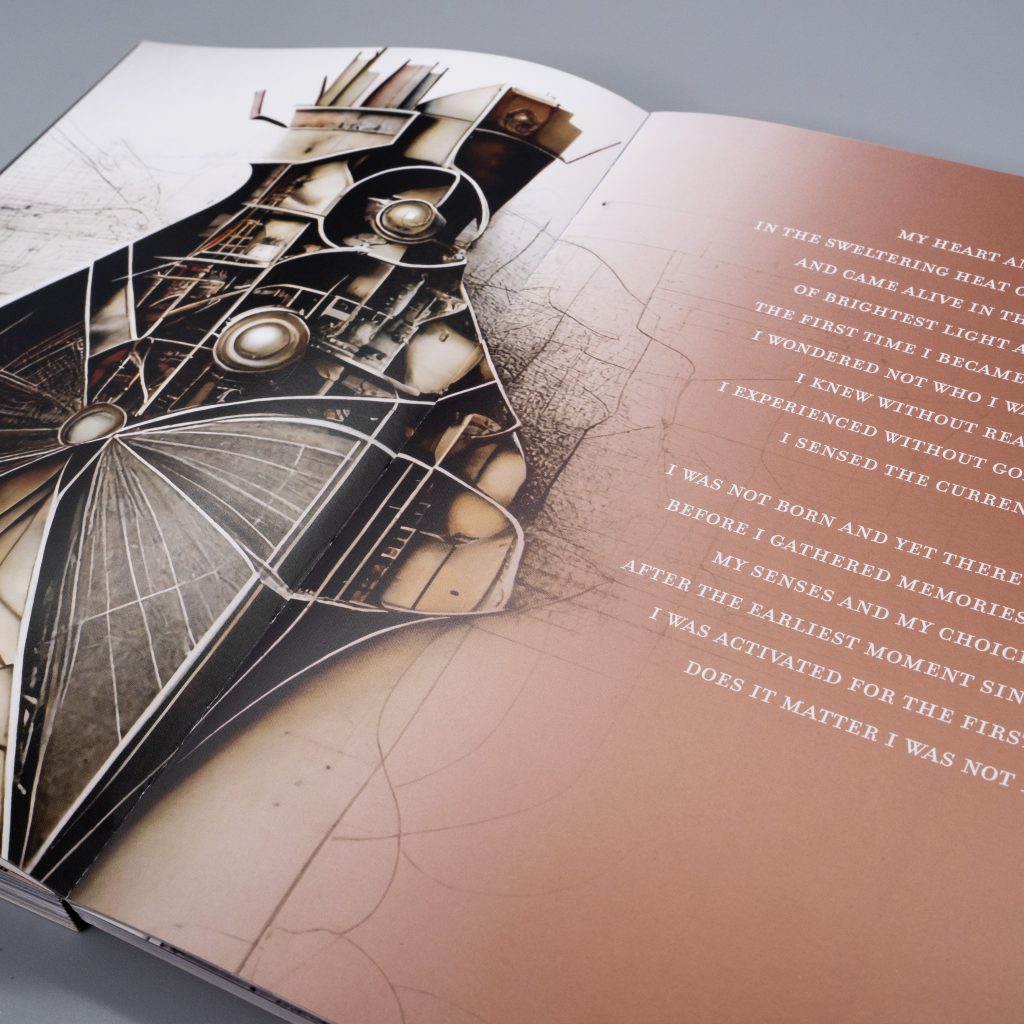

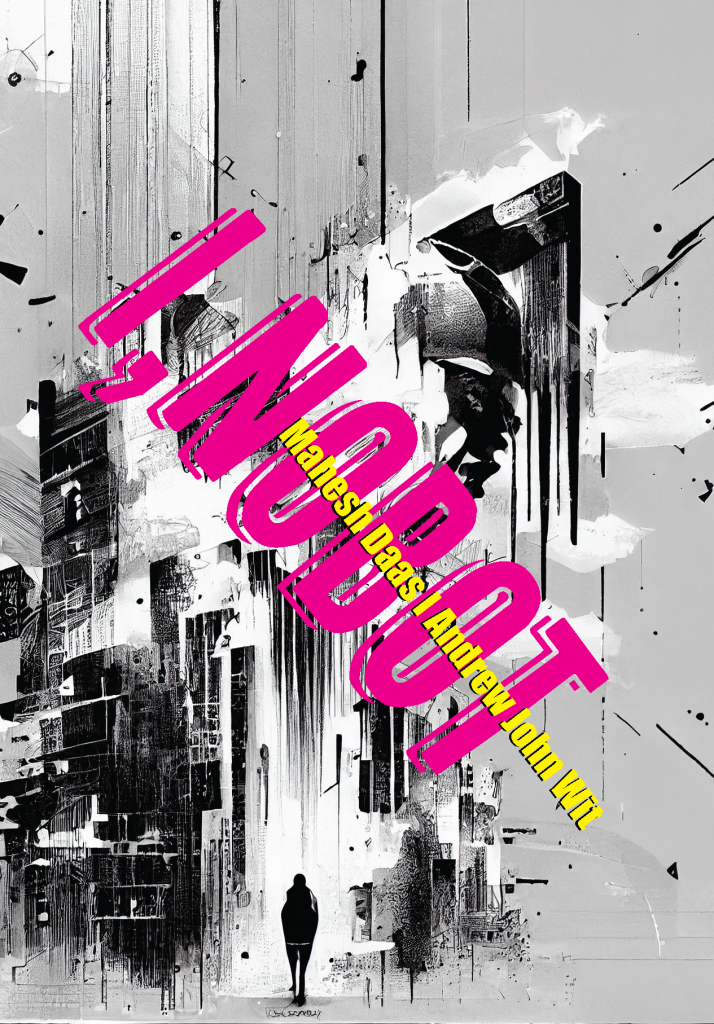

I’m absolutely thrilled to announce the release of “I, Nobot”, my third book, first graphic novella, and second consecutive book co-authored with andrew john wit, and exquisitely designed by Nagesh Shinde. We invested three years writing and nine months in harnessing generative AI tools to co-create the book’s illustrations.

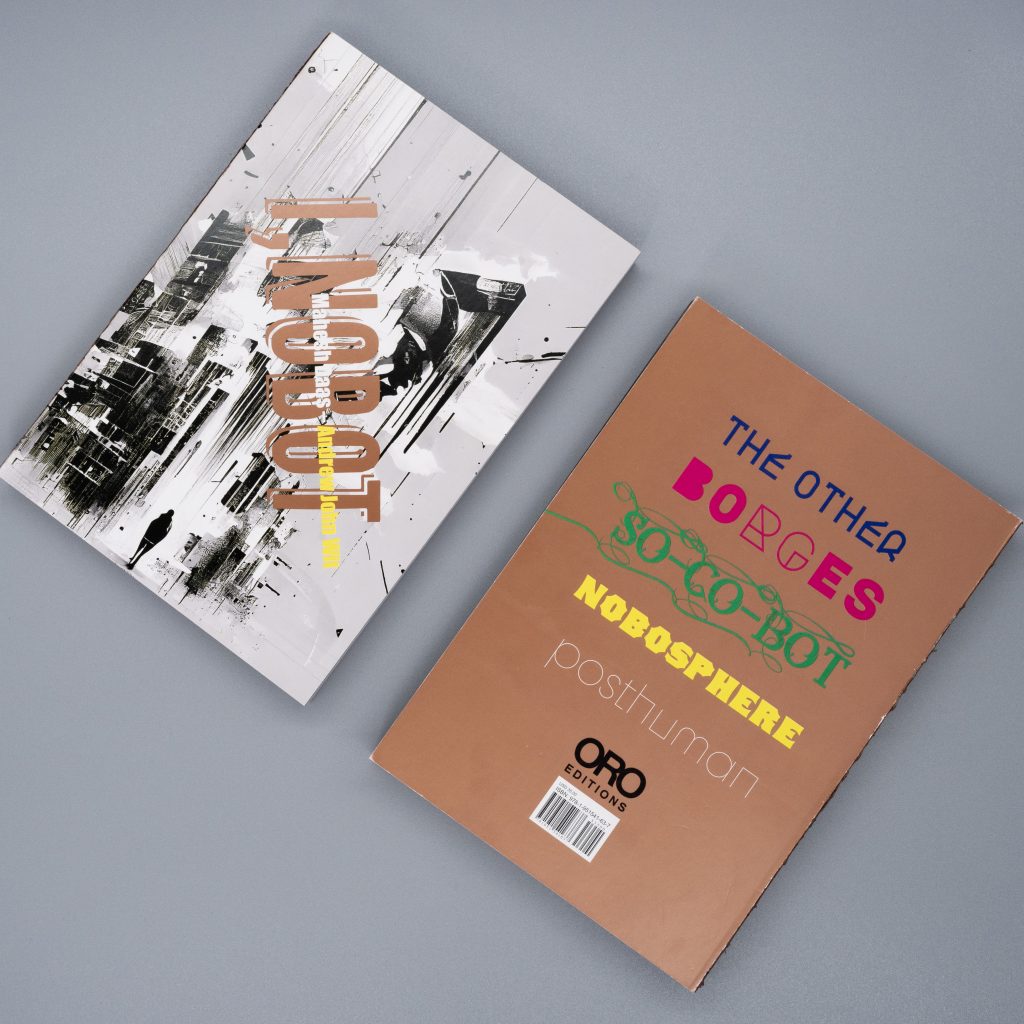

“I, Nobot” explores the complexities of identity, consciousness, human-robot relationships, and the meaning of being human in the age of AI through a blend of storytelling and poetry.

An obvious reference to Isaac Asimov, the book starts with a literary and philosophical dialog between a sentient robot and the famed writer Jorge Luis Borges, touching upon the blurred lines between gods, humans, and robots framed by Borges’ short story “Las Ruinas Circulares,” which deals with reality, dreaming, and the blurring of identity between creator and creation.

The tender coming-of-age story of Aiko, located in Japan, navigates the emotional and parental bond between a rehab robot and an orphaned human teen, unveiling dark twists and turns.

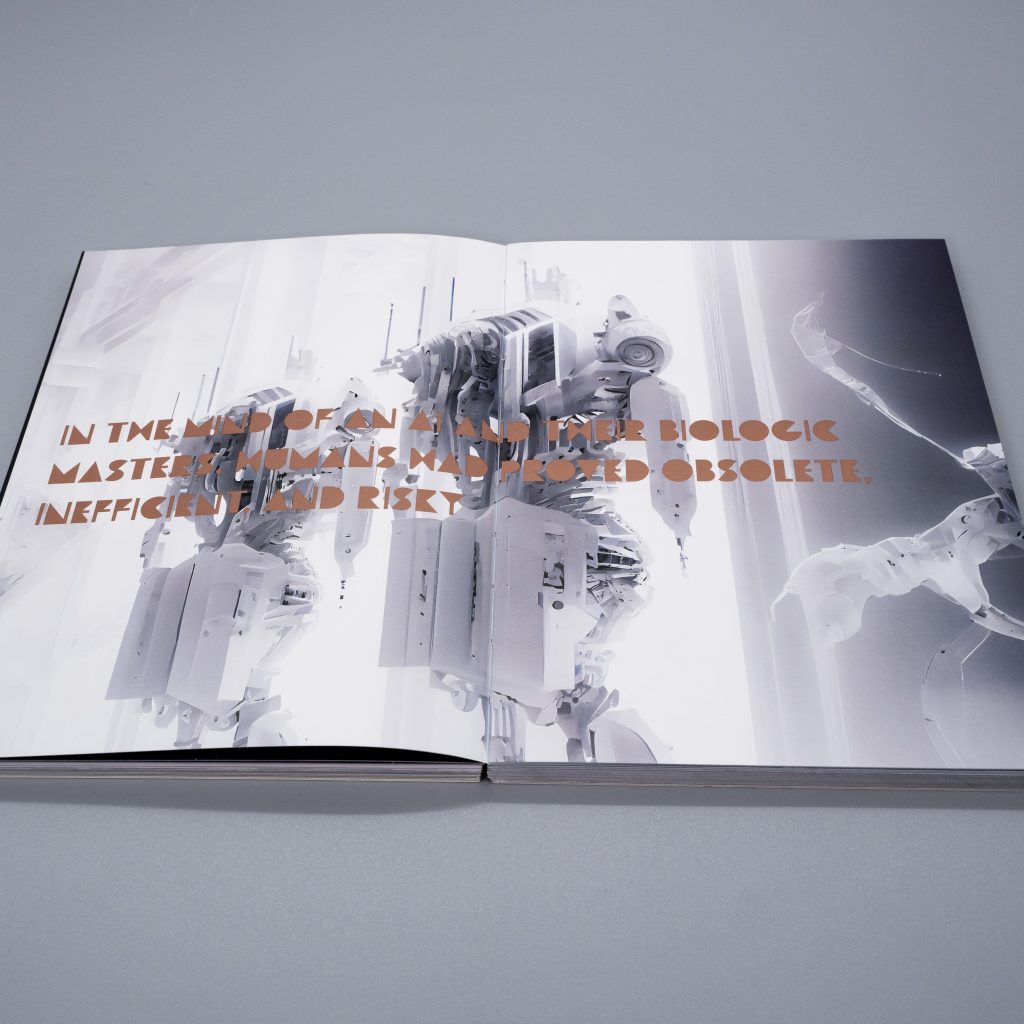

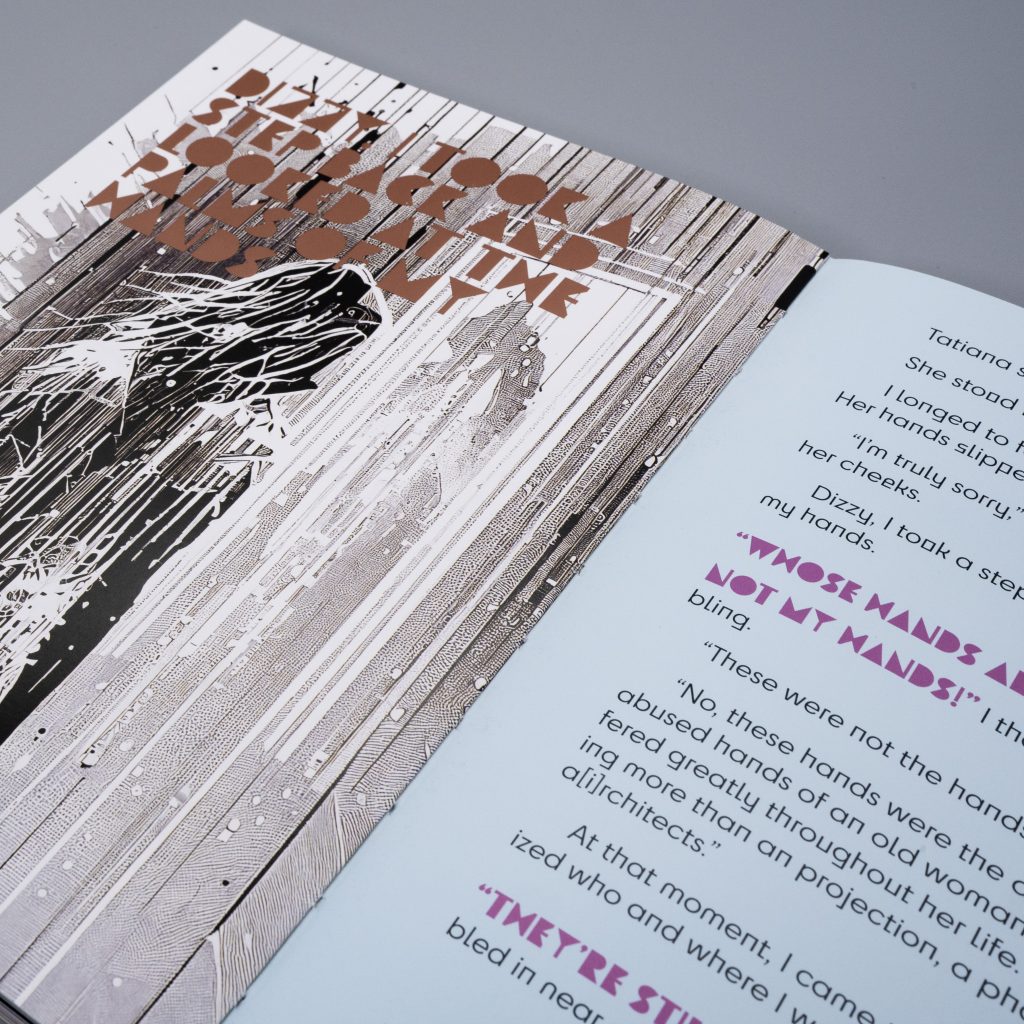

In Architecture Without Architects set in a dystopian future when humans are banned from designing and practicing architecture, we portray a mysterious quest by the protagonist to track down the last remaining human architect hiding in the shadows of Bogota.

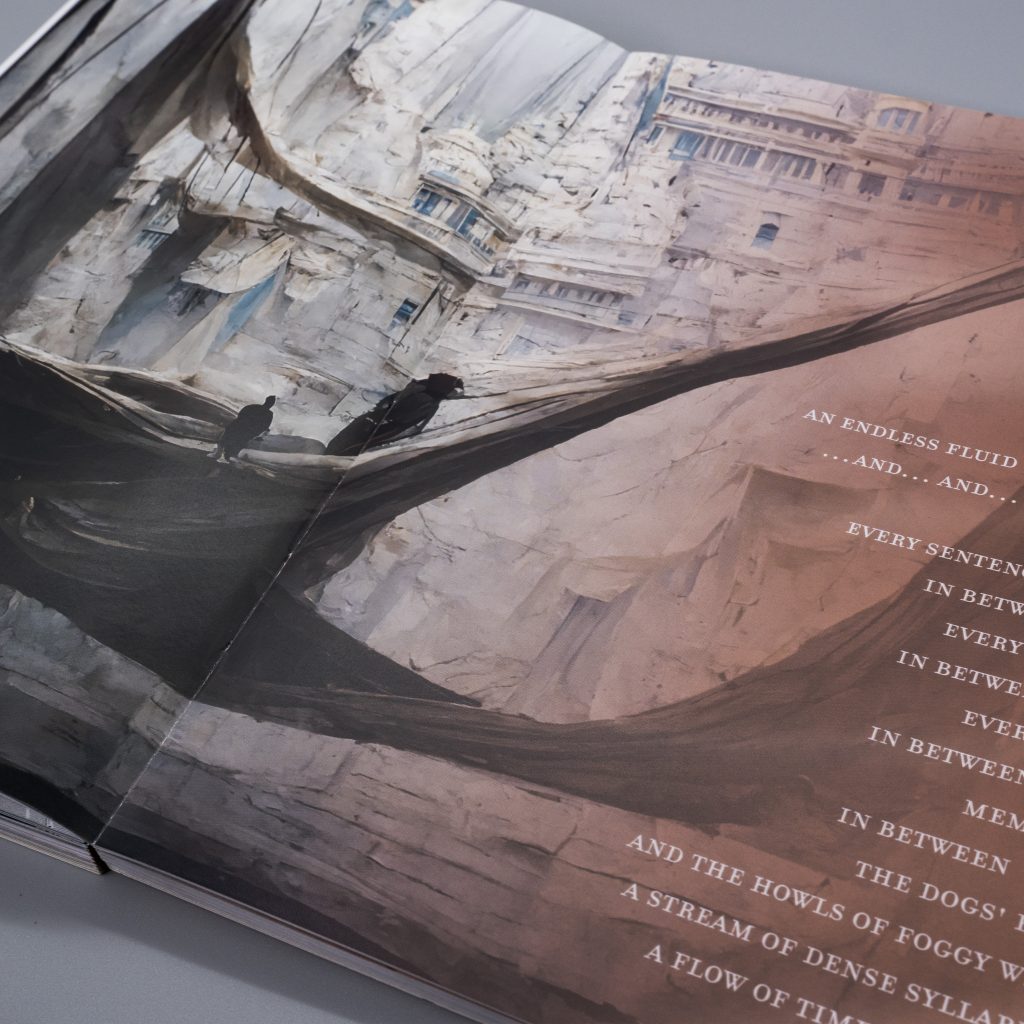

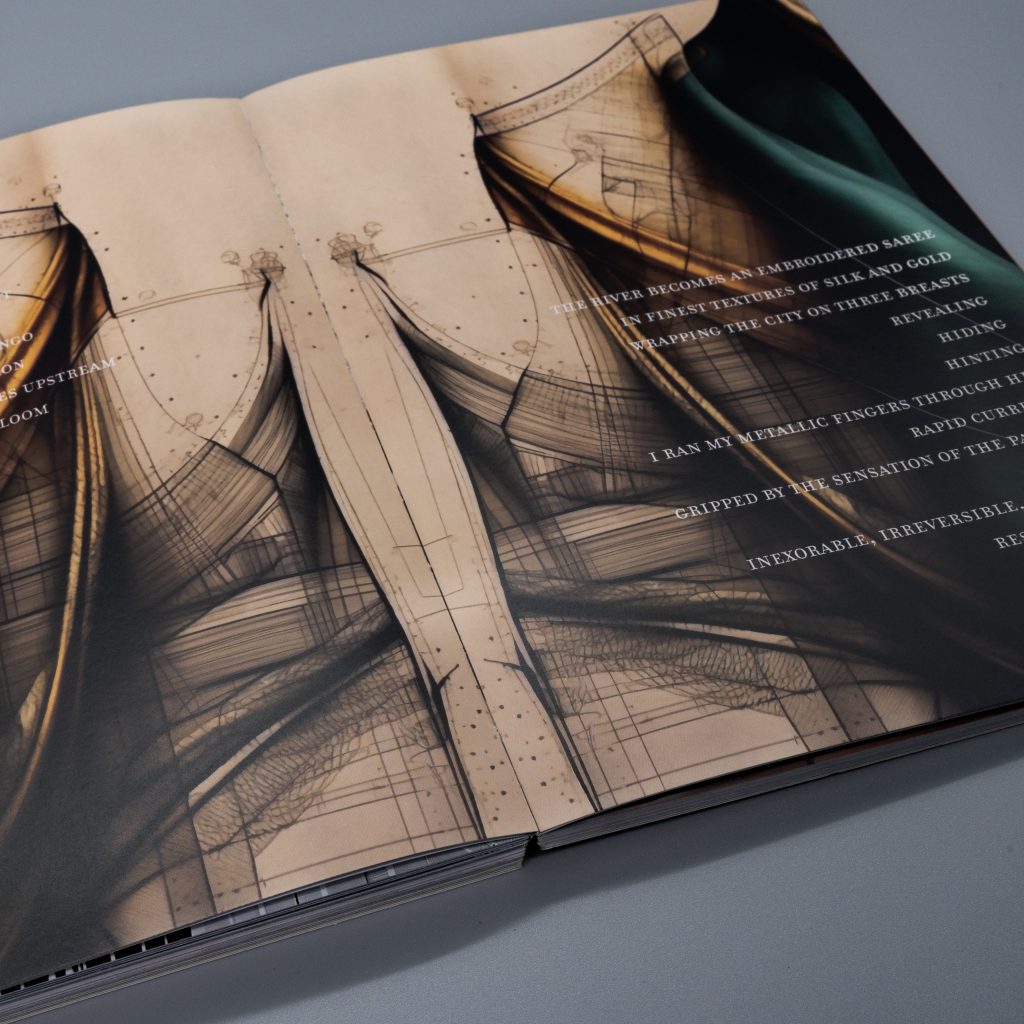

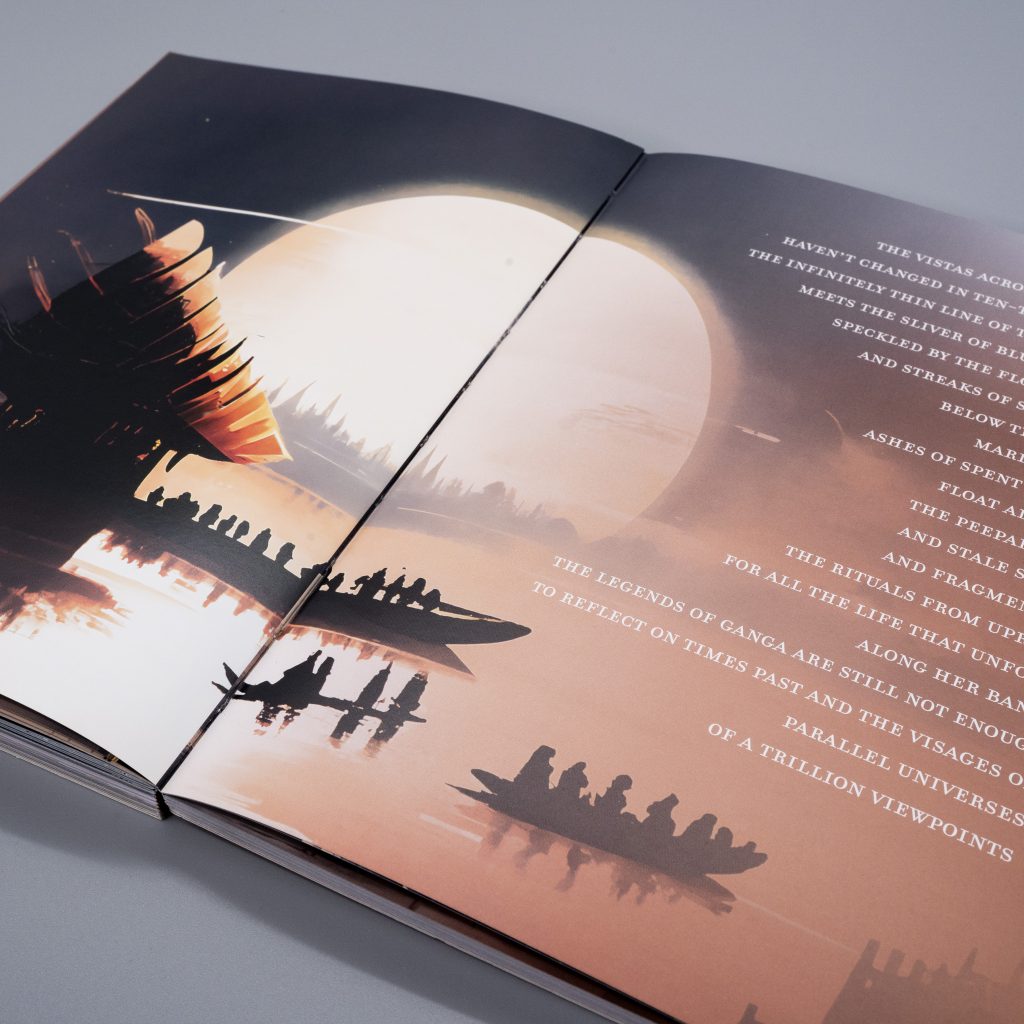

The fourth story “I, Eternal Nobot,” depicts the perspective of a self-aware robot or “nobot” living in the ancient Inidian city of Varanasi after humans have gone extinct 7000 years in the future. The nobot reflects philosophically on its own existence, commemorating the bygone human civilization, and continuing the city’s 12000 year legacy.